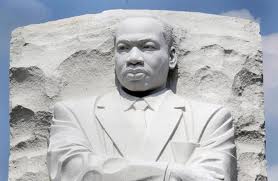

On October 16, 2011, a dedication took place in Washington D.C. for the memorial of the most important civil rights leader in our nation’s history, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King led much of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s, beginning with his involvement in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955.

Dr. King’s birthday, which is celebrated as a federal holiday the third Monday in January, is one of only three federal holidays that honor a person by name, the other two being Columbus Day for Christopher Columbus and Washington’s Birthday for our first President.

The Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial, located near the National Mall in Washington D.C., stands near other commemorations of our country’s most distinguished leaders, such as the Lincoln Memorial, Washington Monument, Jefferson Memorial, and the FDR Memorial. Nonetheless, this solemn memorial reminds us of a grimmer period in America’s history, of an era in the 1950s in which racial discrimination was still customary, in a nation where full civil rights for African Americans did not exist.

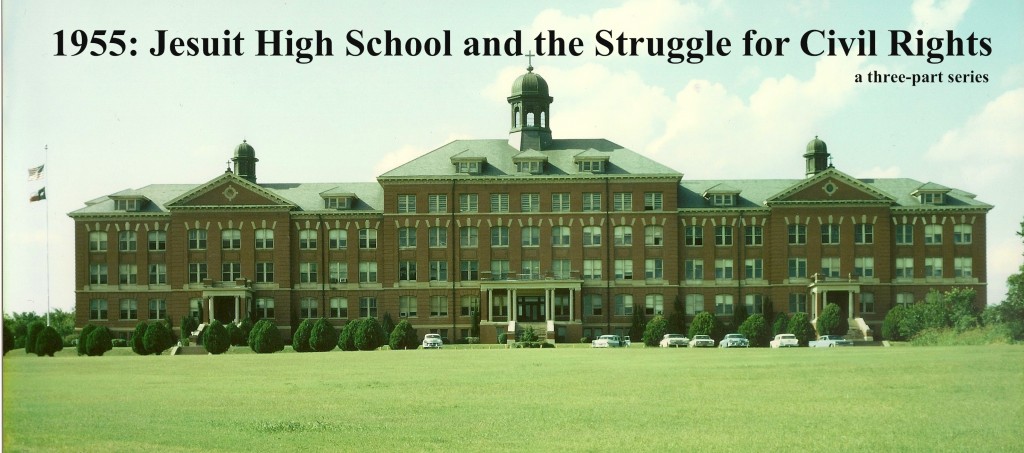

In 1955, during a time when schools were typically segregated and racial discrimination was prevalent all across the United States, Jesuit College Prep, which was then known as Jesuit High School, became the first school in Dallas to enroll African American students, beginning with Charles Edmond ’58 and Arthur Allen ’59.

This is the first article of a three-part series chronicling Jesuit’s small yet significant impact on racial integration of schools in the 1950s. This first part in the series examines the racial climate of the United States during the 1950s, as evidenced by the following events that occurred between the years 1954 and 1956.

Brown vs. Board of Education: “Separate But Equal” No More

Segregation wasn’t an abnormal way of life in the 1950s. What made it so conventional was the enforcement of Jim Crow laws. Enacted in the decades after the Reconstruction era, these laws, aimed at providing a “separate but equal” life for African Americans, often meant that blacks received, among other things, second-rate service and accommodations.

Segregation in the South was enforced de jure, meaning that, by law, citizens had to obey them. Schools, trains, buses, restaurants, motels,movie theaters, water fountains, and court juries—just to name a few—were segregated by law. On the other hand, in northern states, segregation was often de facto, meaning that Jim Crow laws were not authorized, but segregation by race was a recognized and accepted fact of life, or custom. De facto segregation existed in many neighborhoods and churches in the 1950s.

Beginning in the 1890s, many parts of the country, especially the South, became accustomed to maintaining a dual system of education, one structure for whites and another for blacks. This system was declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1954 in the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which overturned an earlier 1896 Supreme Court decision known as Plessy v. Ferguson, which had previously legalized segregation as long as there were “equal” facilities for all races.

Plessy v. Ferguson was based on an incident in 1892 when Homer Plessy, a black man in Louisiana, boarded a train and purposely sat in the “white” section. He was arrested and jailed, but in his case, he argued that his Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated and that he deserved to sit anywhere on the train. However, the Louisiana judge, John Howard Ferguson, ruled that Plessy’s rights had not been violated. As a result, Plessy v. Ferguson institutionalized segregation by law in the South and encouraged towns throughout the South to create more and more laws that segregated the races.

More than sixty years later, Brown v. Board of Education became one of the most momentous acts of the Supreme Court, introducing a major fissure in the structural foundation of Jim Crow, one that would lead to the eventual desegregation of all public schools in the country.

In the original Kansas case, thirteen Topeka parents argued that the “separate but equal” schooling that their children received was anything but equal, calling, in effect, for the abolishment of Jim Crow laws. Challenging school segregation, this case, which was passed unanimously by the nine members of the Supreme Court, overturned Plessy v. Ferguson.

Despite this advancement in the battle against Jim Crow laws, the Supreme Court ruling was not immediately put into effect, and African Americans were still being persecuted primarily by Jim Crow laws. The only way for the ruling to be enforced was if people stepped up and took a stand on segregation. In fact, a few leaders in Dallas, realizing that integration of schools would eventually occur, wanted to show the community that this change could be done at Jesuit High School effectively and without being frightening for society.

Emmett Till: A Trip to the Bottom of a River

The average age of a freshman who enters Jesuit for the first day of school each year is 14. But in the Jim Crow South, life for a 14-year-old black boy could be much more complicated than trying to figure out where your classrooms are on the first day of school. For 14-year-old Emmett Till, in August of 1955, a trip on a segregated train from Chicago, Illinois, to Money, Mississippi, for the summer in order to stay with his relatives may have seemed like a generally harmless event.

A brash young boy of fourteen, Emmett enjoyed juvenile mischief, so when urged by a friend to talk to a white woman one day at a grocery store in that small Mississippi town, he imprudently accepted the challenge.

As he left the store, he called out to the woman behind the counter, “Bye, Baby.” While the woman ran to catch him, Emmett and his friends at the store rushed into their pickup truck, speeding away from the pistol-wielding woman.

Emmett and his friends hurried back home and reminisced about their shenanigans for the next few days. Little did they know, however, that when the woman’s husband, Roy Bryant, returned from his trucking job, he would hunt down Emmett and brutally murder him in the night. His outrageous death would influence people all over the country to push to change customs that had corrupted the country for over 100 years.

Roy Bryant, accompanied by his brother-in-law J.W. Milam, came to the cabin where Emmett Till was staying with his great-uncle Mose Wright. Forcing Emmett to come outside, they grabbed him and shoved him into the back seat of their car. Wright waited for the return of Emmett, whom he thought would just be given a stern but justifiable whipping.

However, after a search for him, Emmett’s mangled body was discovered in the Tallahatchie River. Wrapped around his neck was barbed wire that was tied to a seventy-pound cotton-gin fan. Additionally, he had been beaten severely and shot in the head.

Milam and Bryant, who had been arrested for kidnapping Till, were now indicted on charges of murder. Unsurprisingly, because of Jim Crow laws, during the trial it was an all-white jury that determined in less than 75 minutes that the two men were not guilty.

The two free men, after the trial, later confessed to a magazine reporter for $4000 each. Not able to be charged again because of double jeopardy, Milam and Bryant were never jailed because of the vicious lynching.

Public outrage developed in the media and around the country, causing people to start questioning the harsh laws against African Americans. Even though a Supreme Court decision had stated Jim Crow “separate but equal” laws were unconstitutional, this incident in Mississippi showed what an even greater challenge the country faced in getting states and communities to change their ways of thinking about race and learn how peoples of different races should live in a society mutually.

Rosa Parks: The Lady Will Not Move

Throughout the cities of the South in 1955, people often took the bus, a segregated public transport facility, to and from work. In Montgomery, Alabama, shortly after Thanksgiving, one woman decided she was too tired to live according to Jim Crow laws.

Holiday decorations were beginning to occupy the homes and storefronts of Montgomery, its citizens eagerly awaiting Christmas. The afternoon of December 1, 1955, found Rosa Parks, an African American woman, boarding a bus, about to commute home from work. She entered through the door at the front of the bus, paid the bus fee, and following Jim Crow custom, exited the bus, and walked around to the rear entrance, where she entered and found a seat.

It was like any other day, with Parks, due to Jim Crow laws, sitting in the middle row, a section of the bus that was only open to blacks if a white person didn’t want to sit there. After a short ride, the bus stopped at the Empire Theatre, where some whites hopped on. Almost all the whites found a place to sit; however, one man found his seat taken by Parks. The bus driver, noticing the commotion, advised Parks, “If you don’t stand up, I’m going to have to call the police and have you arrested.” Parks refused to give up her seat, and was subsequently arrested by police officers because of her violation of Jim Crow laws.

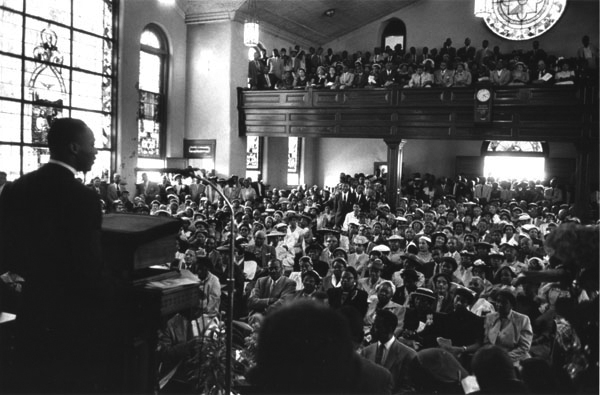

News of her defiance spread quickly throughout the city, and a group of organizers, led by a young man named Martin Luther King, Jr., decided to start boycotting buses in support of Parks’ noble act. A new minister at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Dr. King propelled the yearlong bus boycott with an inspiring speech, calling the citizens of Montgomery to resist nonviolently. African Americans all over Montgomery chose to walk to work instead of riding on a bus.

This series of events, known as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, continued for almost an entire year, until in November of 1956, the Supreme Court condemned Alabama’s bus segregation laws as unconstitutional.

A significant victory in the Civil Rights Movement, the end of segregation on buses showed that racial segregation was very gradually coming to an end, but it was still prevalent in many parts of the country, including Dallas. Because of the work King began at this time, by the time of his death in 1968, Jim Crow laws had been abolished and legislation had been passed by Congress to insure that blacks had full civil rights.

King himself is one of the most important figures in American history, having become a national icon with so much importance that he now stands with other American individuals such as Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Franklin Roosevelt.

Looking Ahead to Part Two in the Series

Delving straight into Dallas, the next article in this series will examine what life in the 1950s was like in Dallas when the city was slowly trying to break away from Jim Crow ways, a period that encompasses the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Emmett Till’s death in Mississippi, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s emergence as a leader of the national Civil Rights Movement that began in Montgomery. During this period, a Dallas Catholic high school run by the Jesuits would play a role in weakening the edifice of Jim Crow here in the City of Dallas.

1955: Jesuit High School and the Struggle for Civil Rights – A Three-Part Series

Sources for this series

“2 Negro Boys Registered by Jesuit School.” Dallas Morning News 3 Sept. 1955.

Allen, Arthur. “Arthur Allen’s Talk.” Jesuit College Prep, Dallas. 2006. Lecture.

Anderson, R. Bentley. “Black, White, and Catholic: Southern Jesuits Confront the Race Question, 1952.” The Catholic Historical Review 91.3 (2005): 484-506. ProQuest. Web. 27 Sept. 2006.

Anderson, R. Bentley. Black, White, and Catholic: New Orleans Interracialism, 1947-1956. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

“Kenny Buddendorff, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

“Color Line Declared Still Law in Texas.” Times Herald [Dallas] 20 Aug. 1955.

Bogen, Harvey. “Negro Group Plans Fair Gate Pickets.” Dallas Morning News 17 Oct. 1955.

Dallas Business Journal, ed. “Stanley Marcus, 1905-2002.” Dallas Business Journal (2002). Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

“Edmond, Charles.” Personal interview. December 2011.

“Jack Eifert.” Personal interview. Dec. 2011.

“Exploring the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial – The Washington Post.” Washington Post: Breaking News, World, US, DC News & Analysis. Ed. Kat Downs. 22 Aug. 2011. Web. Aug.-Sept. 2011. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/lifestyle/mlk2011/interactive-memorial/>.

Eyes on the Prize. Prod. Henry Hampton. PBS, 1987. DVD.

George, Charles. Life Under the Jim Crow Laws. 2000.

George Allen: An Oral History Interview. March 1981.

“Jerry Fagin, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Juanita Craft: An Oral History Interview. Dallas Public Library. 1979

Fowler, Wick. “Attorney Cites Edict of Court.” Times Herald [Dallas] 25 Apr. 1956.

Harper, Jack. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Hopp, James. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Killingsworth, Blake. “”Here I Am, Stuck in the Middle with You”: The Baptist Standard, Texas Baptist Leadership, and School Desegregation, 1954 to 1956.” Baptist History and Heritage (2006). Goliath Business News. Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

King, Martin Luther Jr. “I Have a Dream.” American Rhetoric: The Power of Oratory in the United States. Web. Sept. 2011. <http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm>.

Linden, Glenn M. Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts. 1995.

Murphy, Joseph. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

“McGowan, Richard, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Morehead, Richard M. “Integration Thus Far Affects Few in State.” Dallas Morning News 16 July 1955.

“Negroes Won’t Be Moved.” Times Herald [Dallas] 24 Apr. 1956.

“Pastor Calls for Help to Uphold Segregation.” Dallas Morning News 6 Mar. 1956.

Pettibone, Jerry. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Pitts, David. “Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Decision That Changed a Nation.” Issues of Democracy 4.2 (1999): 38-46. Web. Jan. 2012.

Raffetto, Francis P. “Negroes Ignore Fair Picketing.” Dallas Morning News 18 Oct. 1955.

Schack, William. “Neiman Marcus of Texas: Couture and Culture.” Commentary Magazine (1957).

“Segregation Signs Up Here Despite Order.” Times Herald [Dallas] 10 Jan. 1956.

Seymore, Kelly B. Times Herald [Dallas] 3 Apr. 1988.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 14 Sept. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 31 Mar. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shipp, Bert. “School Integration Not Expected In Fall.” Times Herald [Dallas] 22 July 1956, sec. B. Print.

Stack, John. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Taliaferro, Mike. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965. 15th Anniversary ed. New York, NY: Penguin, 1987.